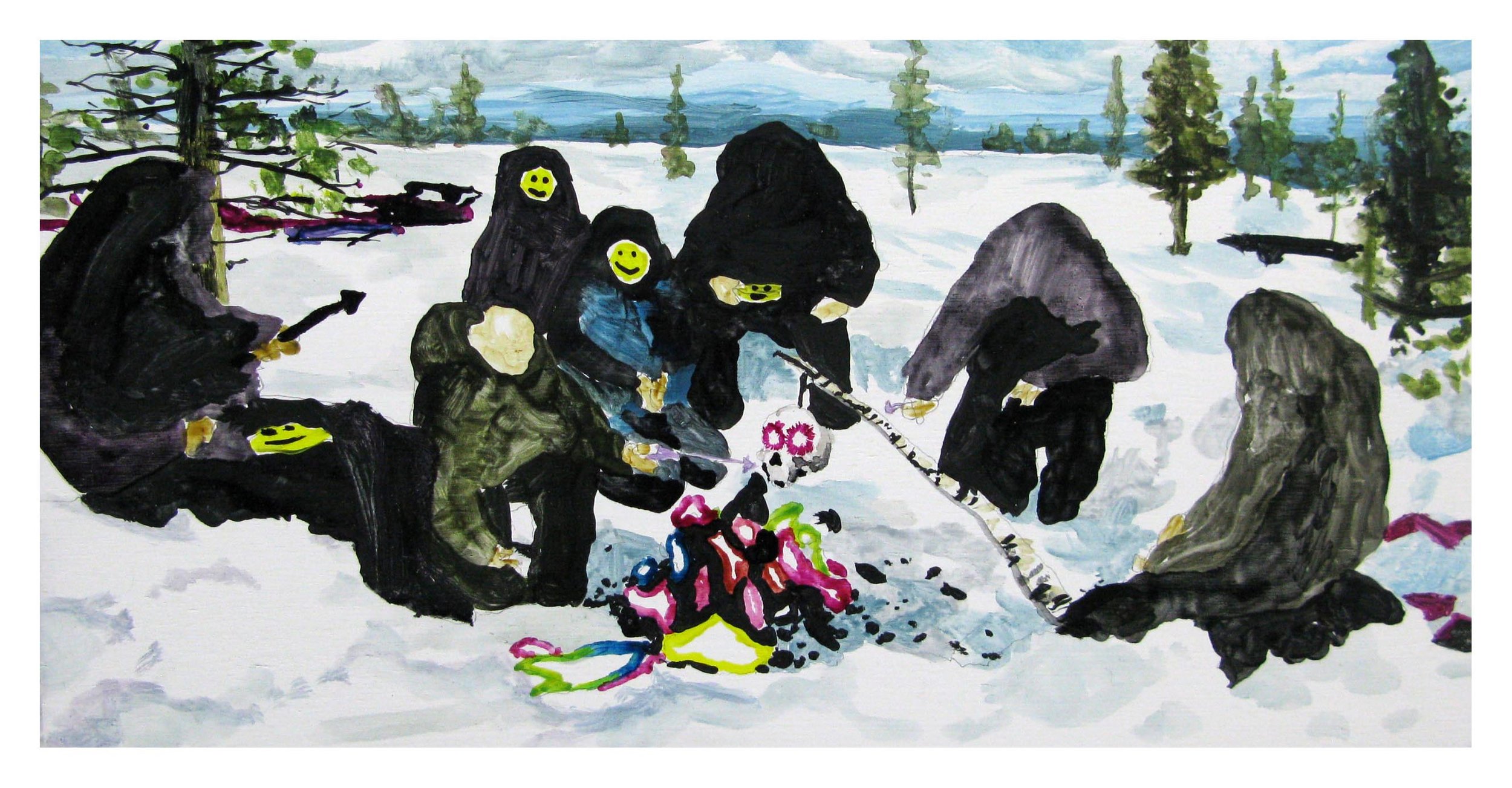

Grant Nimmo, boating trip with techno mum, 2010, oil on German bechwood, 30 x 30cm

Grant Nimmo’s fantastical landscapes take the viewer on a mystical journey to see strangely non-human forms gather among psychedelic forests. We encounter rainbow triangles and smiley faces floating above idyllic scenery of a stream and nearby cottage. We see lumpy figures sitting in a rowboat enscribed with the title “Good” and visit faceless creatures holding basketballs posing for a group portrait. Dreamlike, these strange scenes seem to emerge from the wilderness and simultaneously dissolve in front of our eyes.

An obscure narrative reflects the possibilities of Nimmo’s extraordinary imagination. Yet as his paintings conjure the story of a lost civilization and the environments they inhabitate, the storyline slips away and we are left struggling to grasp the remaining fragments. In part, the elusiveness of Nimmo’s paintings is due to his process of painting on small panels of gessoed wood. The scale and texture of the wood allow Nimmo to work quickly, leaving behind a fleeting impression of his subject. White highlights, which appear as a glare direct from the sun, are created by leaving areas of the whitened surface he is painting thin layers upon. Nimmo’s style typifies a distinctly Australian impressionism, not dissimilar to that of the Heidelberg School artists who worked here in Melbourne during the 19th century. His subjects, like the little girl in Jane Sutherland’s painting “Obstruction” (1887), seem to merge with their outback surroundings to become part of the natural environment. However, unlike the Heidelberg School artists who enjoyed painting outdoors, or en plein air, it is an important distinction that Nimmo does not paint directly from nature itself. What makes his work interesting is that he works two steps away from nature; painting instead the idea (and the idealization) of the landscape.

Nimmo scours the internet, books and magazines for images of romantic landscapes. Initially, in a 2006 exhibition entitled Natura, these scenes were of popular film stills (Lord of the Rings, The Deer Hunter), although now Nimmo works mostly from generic pictures of natural environments. Already one step removed from nature, he then paints from these found images and through a process of addition or subtraction pushes them towards artificiality. Faces are dissolved, technicolour clothing is added and then, like a computer screensaver, Nimmo’s scenes become idealized images of a nature imagined.